Confronting life, love, and liberation with a style by Azfar Hussain

1992—1995. I was then General Secretary of Bangladesh Lekhak Shibir, a national organisation of writers and activists on the left. Akhtaruzzaman Elias—our major fiction-writer in the Bengali language—was its Vice-President. Although way older than me, he treated me like his friend and comrade. With him I had countless conversations that free-ranged within a broad zodiac of issues and concerns from politics to philosophy to poetry to history to fiction. It was he who urged me to read and re-read another fiction-writer's work, assuring me in more than one conversation that his work would keep me going in several, even contradictory, directions, and would make me not just feel but think and rethink the brute things of life, although, according to Elias, he is by no means a cerebral writer. Elias called him “Botu Bhai.” Elias also recalled his freewheeling, vibrant, even deeply contentious, moments at Rex Restaurant and Beauty Boarding—sites that became some writers' hangouts in the late sixties—sites that poets like Shahid Quadri and Rafiq Azad and the proverbial Buro Bhai [Mosharrof Rasul], among others, frequented. Botu Bhai used to be there too.

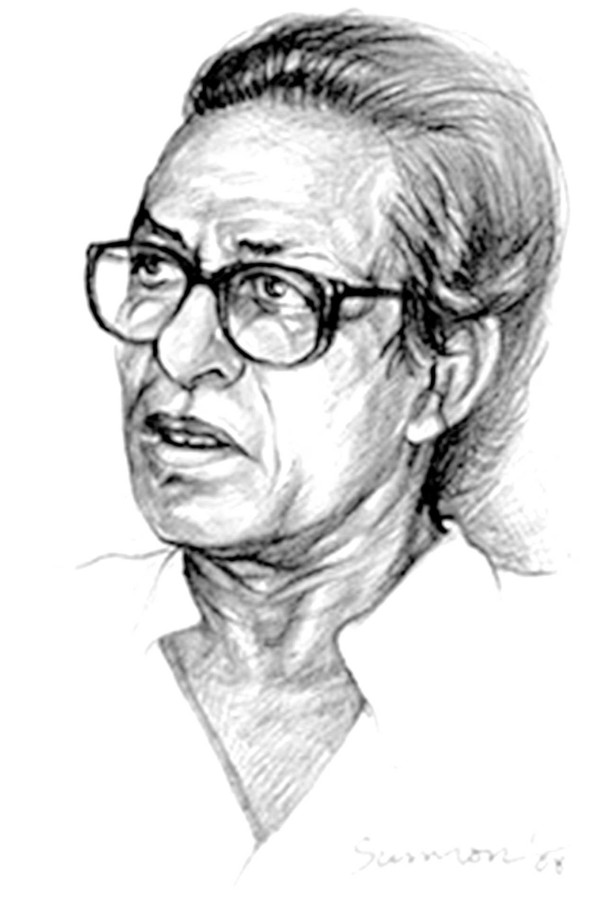

Affectionately called Botu or Botu Bhai by his friends and others, he is none other than Mahmudul Haque (1941-2008)—one of the most powerful fiction-writers from Bangladesh. July 21 marked his ninth death anniversary. Mahmudul Haque wrote and remained silent equally remarkably in his lifetime. And when he wrote, he wrote productively, even intensely, with a peculiar passion untrammeled by momentary vicissitudes. He wrote most of his novels at one stretch, taking a week or two. He wrote one novel even in a single day. I think this “mode of production” is rare in the history of the Bengali novel. Of course, Haque's novels do not have epical amplitude. But by no means, then, was he simply trying to crank out stuff; he ended up producing landmark novels in almost headlong succession.

Affectionately called Botu or Botu Bhai by his friends and others, he is none other than Mahmudul Haque (1941-2008)—one of the most powerful fiction-writers from Bangladesh. July 21 marked his ninth death anniversary. Mahmudul Haque wrote and remained silent equally remarkably in his lifetime. And when he wrote, he wrote productively, even intensely, with a peculiar passion untrammeled by momentary vicissitudes. He wrote most of his novels at one stretch, taking a week or two. He wrote one novel even in a single day. I think this “mode of production” is rare in the history of the Bengali novel. Of course, Haque's novels do not have epical amplitude. But by no means, then, was he simply trying to crank out stuff; he ended up producing landmark novels in almost headlong succession.But, later on in his life, Haque stopped writing. His silence seemed mysteriously stubborn and was even audible like a waterfall: he wrote almost nothing over a period of 28 years! In an interview, he told us: “After 1980, I wrote nothing.” In another interview, however, Haque told us how Vidyasagar withdrew himself from a writer's "career" towards the end of his life, and how Jagadish Chandra Bose stopped talking to people later in his life. He even indicated that Kazi Nazrul Islam was not silenced in the final instance, but had chosen to be silent probably to endure the unendurable, to live the unlivable, in the face of the Real (or the Big Truth), inaccessible as it is to language or the symbolic order of things. I'm not sure if Haque was comparing his predicament to theirs—or maybe his invocations of the trinity of figures here adumbrate a purely metaphysical turn in his life—but thinking of Mahmudul Haque's sustained silence, I wrote at a very young age a poem titled “Tentative Textures of Silence,” some lines from which I can't resist quoting here:

“Silence is not a thin glass

You cannot break it,

Neither can I

For silence is a country of forever-fumbling

Trying to hint at

The last syllable of a lost word.”

Hints, suggestiveness, silences, inconclusiveness, even painful ambiguities surrounding personal loss, and bristling incertitude decisively characterise at least part of what I wish to call the poetics of Haque's fiction—an issue I intend to take up later. Haque is, among other things, surely a poet in his prose, remaining permanently drawn to Western figures like Baudelaire and Pasternak, while he fiercely commended the power of the major Bengali novelist Manik Bandopaddhay without, however, being influenced by him. He also deeply admired another major Bengali fiction-writer—Komol Kumar Majumder. Further, Haque delighted in the work of the Mexican fiction-writer Juan Rulfo, one of whose poems he even translated into Bengali.

His silence notwithstanding, Haque already left us nothing short of a memorable constellation of fictional works: seven novels, two collections of short stories, and a novel for adolescents and adults alike. He also left behind many unpublished and uncollected stories. In fact, Haque began by writing short stories, and his first story called Durghotona appeared in the magazine Sainik in 1953. His first published, if not first, novel is called Anur Pathshala, later renamed Jekhane Khonjona Pakhi. It was written in 1967, but it appeared in 1973. With its publication, Haque immediately made his mark. Its style rather than its structure then appeared striking. His other novels include Nirapod Tondra (1974), Jibon Amar Bon (1976), Khelaghor (1988), Kalo Borof (1992), Matir Jahaj (1996), and Oshoriri (2004). Each novel he wrote is astonishingly new in its own way, while Haque himself is already known for saying: “I wanted to transcend myself in every instance.” Of course I cannot do justice to the entire range and the richness of Haque's works in a short piece like this one. All I can do is call attention to only a few aspects of his works that I find intriguing and significant.

***

By no means a traditional storyteller, not even an immediately captivating or spell-casting one, Mahmudul Haque is undoubtedly a powerful novelist who tends to disturb and disrupt the continuum of conventional assumptions about life, society, politics, and history. He does not weave or interweave tales in the manner of, say, a Gabriel García Márquez or our Akhtaruzzaman Elias. He selects, carves, crafts, even modulates stories and events—subjects, sites, scenes, and signs—to make us pause and think about that which has taken place—the concretely sensuous, that is—and about what philosophers call “the non-empirical essence of all reality.” His works give us the impression that human beings themselves are not finished products but processes, and that such processes are not continuous but fractured, fissured, even punctuated. Love in Haque's world is probably the most difficult and challenging thing, yet it is possible. And when it is possible, it is liberating. Interestingly, his novel called Khelaghor—which is about love in the time of war (our Liberation War of 1971)—reveals that even love itself is political.

Haque's characters—both atypical and representative from a social standpoint—are usually alienated, alienating, sick, sickening, displaced, yet energising and life-giving under certain circumstances. Alienation and displacement constitute the two foremost abiding concerns for Haque in his works of fiction. One would do well to remember that Haque was born not in Bangladesh but in Barasat, 24 Paraganas, and that, with his family, he moved from there to Dhaka three years after the partition of 1947, when he was only ten. By his own admission, this was a painful displacement with all its complexity. I think this displacement has at least a three-fold implication for Haque's fictional work as a whole: personal, political, and linguistic. One sees all this in a number of his novels, his short stories included, particularly in his major novel called Kalo Borof.

"What I think fundamentally characterises the totality of Mahmudul Haque's work is his creative triangulation of story, memory, and history. These three things are indeed creatively and profoundly intertwined in his works ranging from Anur Pathshala, through Jibon Amar Bon and Kalo Borof, to Oshoriri.

Of course, Haque and his middle-class family suffered psychologically and financially due to this displacement—both spatial and temporal—while it also brings up the question of how communalism itself has come to characterise the mainstream, ruling-class politics of nationalism from at least the 1905 “Partition of Bengal” through the 1947 partition of India to the post-independence period in Bangladesh. Further, this displacement for Haque turns language itself into a site of struggle: Haque, as he admitted, had to learn and pick up the particular syntax in which to write in Bangladesh, while he of course actively responded to dialects in Dhaka, both “kutti” and “Dhakaiya” (these two are not the same thing), that he uses in his novels to varying degrees and effects. Of course, Haque's works are not strictly autobiographical; the autobiographical is never mechanically mediated in them. Yet the autobiographical is variously refracted in his stories and novels.

I think Haque's works of fiction are rich examples of creative tensions and transactions among his childhood's West-Bengal Bengali, the new syntax learned in Bangladesh, the dialects made available to him in Dhaka, his own novelistic diction —shot through with sense-shaking poetic metaphors—and his own middle-class urban sensibility, which together come to constitute and characterise Haque's stylistic disposition, thus making him different from two other powerful fiction-writers from Bangladesh—Hasan Azizul Huq and Akhtaruzzaman Elias. I also think there's something Conradian about Haque's style: self-conscious, sometimes withdrawn and alienating, sometimes even disconcerting, yet both beautiful and powerful.

What I think fundamentally characterises the totality of Mahmudul Haque's work is his creative triangulation of story, memory, and history. These three things are indeed creatively and profoundly intertwined in his works ranging from Anur Pathshala, through Jibon Amar Bon and Kalo Borof, to Oshoriri. There are stories of memories and memories of stories, particularly, if not exclusively, in two of his major novels—Jibon Amar Bon and Kalo Borof. The role of memory is indeed vital in Haque's work. But memory does not serve as an escape route but is a powerful mode of confronting and re-living a life that is ostensibly unlivable. To use the German Marxist cultural critic Walter Benjamin's idea, memory for Haque is not a simple, linear process of remembering but a “struggle to recall” in a set of images, geared towards making sense of and even transforming the autobiographical fragments Haque uses in his novels.

As for history, Haque does not claim to mobilise so-called authentic historical narratives and chronologies as such. For him, like memory, history, too, resides in flashes, in images, in “dialectical images,” as Benjamin would say. History also resides in crucial events. The novel Jibon Amar Bon in particular seems to be attesting to Antonio Gramsci's famous formulation: “Events are the real dialectics of history.” To speak of events for Haque, then, is to speak of two crucial years with which his novels remain repeatedly concerned one way or another: 1947 and 1971—the year of the Partition of India and the year of the National Liberation War of Bangladesh. In fact, Mahmudul Haque has given us at least one of the best novels surrounding the Liberation War of 1971—Jibon Amar Bon.

An alternative but careful and diligent reading of the above-mentioned novel reveals, contrary to the popular contention, that it is not the middle-class, indecisive individual named Khoka who is the actual protagonist of this novel but the masses themselves—ones who are both makers and victims of history. But Haque does not romanticise the masses; he even sees their pitfalls and their aberrations; yet Haque sides with them, indicating on more registers than one that liberation itself is a tragically unrealised dream. Language itself then becomes a weapon in his creative struggle against everything that produces and reproduces alienation which is not only existential but also political. Indeed, broadly speaking, the question of human liberation—in more senses than one—remains at the heart of Mahmudul Haque's creative enterprises. I think it is this Mahmudul Haque we are yet to explore fully—a fiction-writer who enacts a productive dialectic between aesthetics and politics in the interest of love, liberation, and life itself.

0 comments:

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.